How to Build an Internal Carbon Buying Rulebook: Workflows, Roles, and Governance Models

Table of contents

1. Introduction: The Gap Between Climate Ambition and Execution

2. Why Carbon Procurement Is Harder Than Traditional Procurement

3. Core Components of a Carbon Buying Playbook

Strategy Alignment

Evaluation Criteria

Procurement Workflow

Governance

Claims & Reporting

4. Step-by-Step: How to Design a Carbon Procurement Playbook

Step 1: Define the Strategic Role of Credits

Step 2: Build a Portfolio Mix Framework

Step 3: Establish Standardized Integrity Criteria

Step 4: Set Governance & Decision Authority

Step 5: Define Claims & Reporting Guardrails

5. Operating Workflow Example: Turning Process Into Practice

6. Common Failure Modes — And How to Avoid Them

7. What “Good” Looks Like: Signals of a Mature Carbon Buying Function

8. The Role of Hestiya in Enabling High-Integrity Carbon Procurement

9. Conclusion: From Climate Commitments to Credible Execution

1. Introduction: The Gap Between Ambition and Execution

The ambition of corporate climate action has increased tremendously over the past five years. Thousands of companies have set net-zero target. For example the Net Zero Tracker shows that the number of large firms with such targets rose by over 40 % in 16 months (from 702 to 1,003) covering US $27 trillion in annual revenue. Yet, in most cases, there is no action to support those commitments: one study found only 16 % of the world’s largest companies are on track for net-zero by 2050, while nearly half are still increasing emissions.1,2

Often, it is not the intent that is lacking. Sustainability and procurement leaders are motivated, serious, and recognize the stakes involved. Instead, the challenge is operational clarity. Carbon procurement is today fragmented across sustainability, procurement, finance, legal, and risk teams. Each team has fragments of the process - few have a collective, repeatable process that enables all the stakeholders to review, compare, approve, and retire carbon credits without uncertainty.

With rising expectations, these gaps are expanding. Credibility and traceability have been raised by new frameworks which set a higher bar:

The SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard 2.0 (Consultation Draft)3 going beyond the setting of targets for performance tracking and claims.

ICVCM's Core Carbon Principles (CCPs)4 introduced additional thresholds of quality.

VCMI's new Claims Code of Practice strengthens how the use of carbon credits is disclosed to the public.5

At the same time, sustainability teams are increasingly under-resourced. The voluntary carbon market is still early stage (McKinsey estimates only ~US $300 m in 2020) and yet demand could multiply 15× by 2030 or up to 100× by 2050, creating a significant operational burden.6

This is why a carbon buying playbook is no longer a “nice to have” it is now core to credible net-zero delivery. Organizations, now more than ever, require a structured, evidence based workflow by which to source, diligence, select, and monitor credits in a way that can be defensibly communicated internally and publicly.

This is where Hestiya comes into play: allowing teams to operationalize high-integrity carbon procurement through standardized evaluation frameworks, clear governance, and expert support, so climate ambition can turn into action.

2. Why Carbon Procurement Is Harder Than Traditional Procurement

Carbon credits should not be viewed as a single product category. There are multiple types of carbon credit interventions, with varying durability, measurement methods, and risk profiles. Unstandardized credit types: such as avoidance, reduction, removal, nature-based, and engineered solutions lack an agreed-upon framework for assessment, as noted in the SBTi Net-Zero Foundations guidance.3

Project types and registries differ significantly in methods and robustness of verification and assessment, as noted in the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles framework.4

The data is still disaggregated across registries, trading brokers, and public-facing platforms, making traceability and due diligence cumbersome, as discussed in the World Bank’s State of the Voluntary Carbon Market report.6

The market, based on evidence in the Trove Research VCM Market Outlook, continues to be opaque, price is not an adequate indicator of quality or durability.

Internally, Sustainability, Procurement, Finance, and Legal often have different requirements and risk tolerances, hindering decision-making, as described in McKinsey’s Blueprint for Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets report.

The majority of organizations' slow pace of decision-making is often the result of workflow friction from ambiguous authority, differences in screening criteria, redundancies in reviewing and assessing credits, and fragmented evaluation responsibility. When organizations establish a common evaluation framework and an aligned and repeatable procurement workflow, the speed, affordability, and integrity of carbon surface buying could be improved.

3. The Core Components of a Carbon Buying Playbook

As organizations transition from climate intentions to action, they require a repeatable, defensible structure with regard to procuring carbon credits. A Carbon Buying Playbook establishes that structure. Rather than relying on informal or personalized knowledge, the playbook provides guidance on how to identify, assess, acquire, and disclose credits, representing a unified approach with Sustainability, Procurement, Finance, and Legal.

4. Step-by-Step: Designing the Playbook

Creating a Carbon Procurement Playbook is focused on converting climate ambition into a repeatable, defensible, cross-functional procurement process. It’s about not just buying credits, but buying the right credits with consistency, transparency, auditability, and clarity for both internal and external stakeholders. Below is suggested framework on how to build the playbook.

Step 1: Define the Strategic Role of Credits

As a first step, you must clarify the role of carbon credits can play in your net-zero pathway. Carbon credits should not replace your own internal decarbonization initiatives; credits will act as a complementary measure for residual emissions, transitional gaps and value-chain limits where emissions reductions will not happen yet. This is congruent with how the Science Based Targets initiative frames credits — as one facet of a staged and path-oriented approach toward decarbonization.

Organizations should also seek to align their claims and use of credits with stakeholder trust frameworks such as the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) or project quality screening norms such as the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles.

Next, boundaries of eligibility need to be defined rules that illustrate what kind of credits are acceptable to the organization. Eligibility boundaries may include some of the following:

Minimum durability thresholds (e.g., >30 years of permanence for forestry, 1,000+ years durability for engineered removals)

Geographic relevance (e.g., credits that are located in regions that the company operates in or credits that support value-chain resilience in appropriate geographic regions)

Alignment with corporate sustainability values (e.g., credits that provide community benefits, engage biodiversity, or involve indigenous co-governance)

These eligibility boundaries help to mitigate arbitrary exceptions while ensuring that the portfolio is consistent across multiple procurement cycles and organizational leadership.

Step 2: Build a Portfolio Mix Framework

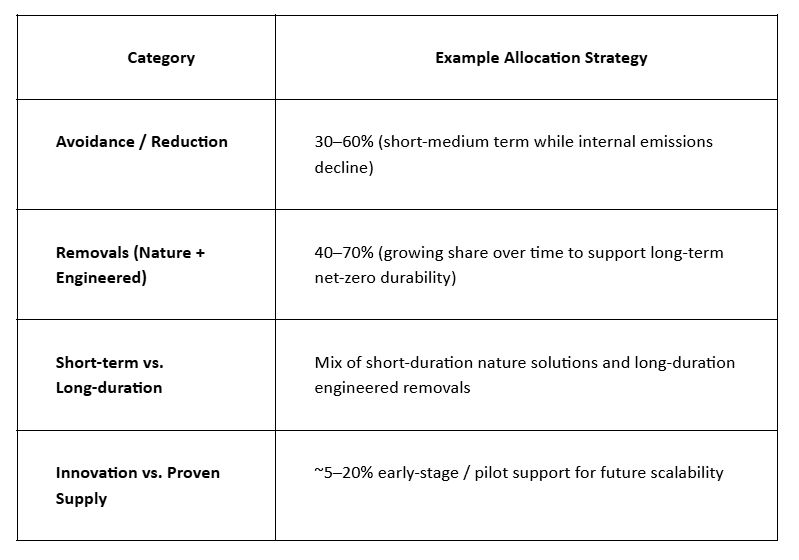

Once eligibility is defined, the organization needs a portfolio strategy. Rather than buying credits opportunistically, define target allocation ranges, for example:

This framework should incorporate portfolio trajectories over time to ensure that as internal emissions decrease, the portfolio inclines toward increasingly durable removal solutions, as indicated by the guidance for net-zero in the IPCC’s reported Guidance for Long-Term Mitigation Plans and the SBTi Net-Zero Standard.

Example trajectory (high-level idea):

Today (High Footprint) → Combination of avoidance + nature removals

2030 (Reduced Footprint) → Mostly removals + some early engineered removals

2040-2050 (Residual Emissions Only) → Mostly high-durability engineered removals

This stage establishes intention: to help guarantee that purchases are consistently evolving with decarbonization process, instead of sitting still.

Step 3: Establish a Standardized Evaluative Rubric

Quality varies widely across the spectrum of carbon projects — so evaluation should be standardized. A strong evaluative rubric often includes categories such as:

Additionality: Would the climate benefit have accrued in the absence of this project?

Permanence/Durability: What is the timeframe of storage and reversal risk for carbon?

Rigour of MRV (Measurement, Reporting & Verification): how cautious in certainty is the data evidence?

Leakage risk: Would the benefits that result from this project lead to negative impacts in another area?

Co-benefits: (biodiversity, or livelihoods, or local community outcomes, etc.)

Free, Prior & Informed Consent (FPIC) for nature and indigenous land projects

This rubric should be based on existing criteria such as the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles and recommendations from the Gold Standard and Verified Carbon Standard (VCS).

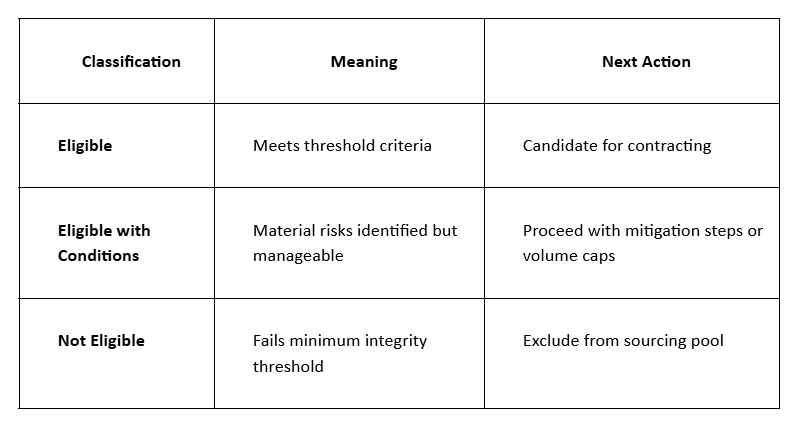

Third-party quality ratings (e.g., from carbon ratings agencies) are helpful inputs, but organizations should validate underlying assumptions internally to ensure ratings align with internal values, risk tolerance, and reporting requirements. To make evaluation outcomes actionable, introduce a three-tier project decision classification:

This transforms subjective judgment into a repeatable scoring process.

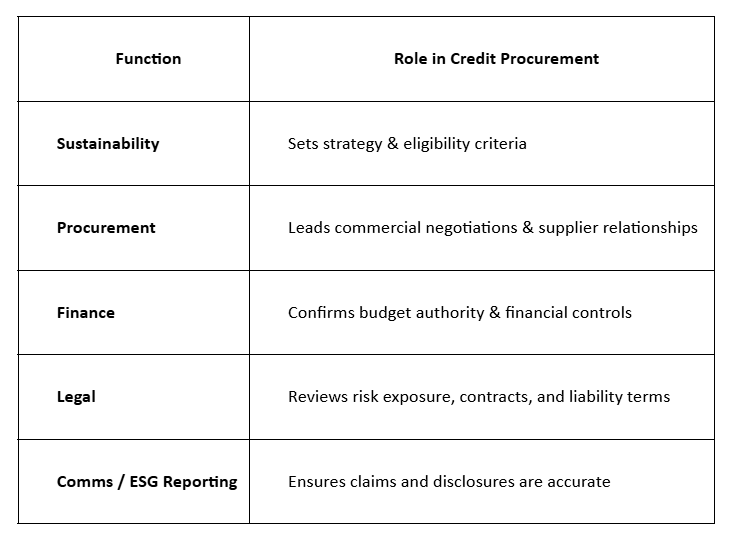

Step 4 — Establish a Governance Model

Governance defines who does what, and prevents procurement bottlenecks.

Introduce a RACI matrix across core functions:

Additionally, document decision triggers and approval thresholds, e.g.:

≤$250K - Sustainability + Procurement approval

$250K or Multi-Year Commitment - Executive Sustainability Committee approval

Creating clear delegations prevents the escalation loops or last-minute delays. Governance models of this type are in alignment with the operating practices suggested in McKinsey's voluntary carbon markets guide.

Step 5 - Define Claims and Reporting Guardrails

Ultimately, the playbook must specify how are credits communicated both internally and externally.

Tie credit retirement timing to annual emissions reporting timing.

Be sure credentials align with VCMI Claims Code of Practice, which outlines guardrails on language.

Don't use marketing language framing the environmental impact of your product wildly out of context (e.g. "carbon neutral product" without evidence).

Offer sustainability and comms teams templates and guidance about messaging to mitigate accidental misrepresentation.

Trust in the consistency of claims is critical in protecting against regulatory and litigation risk and maintaining stakeholder trust.

5. Example Operating Workflow

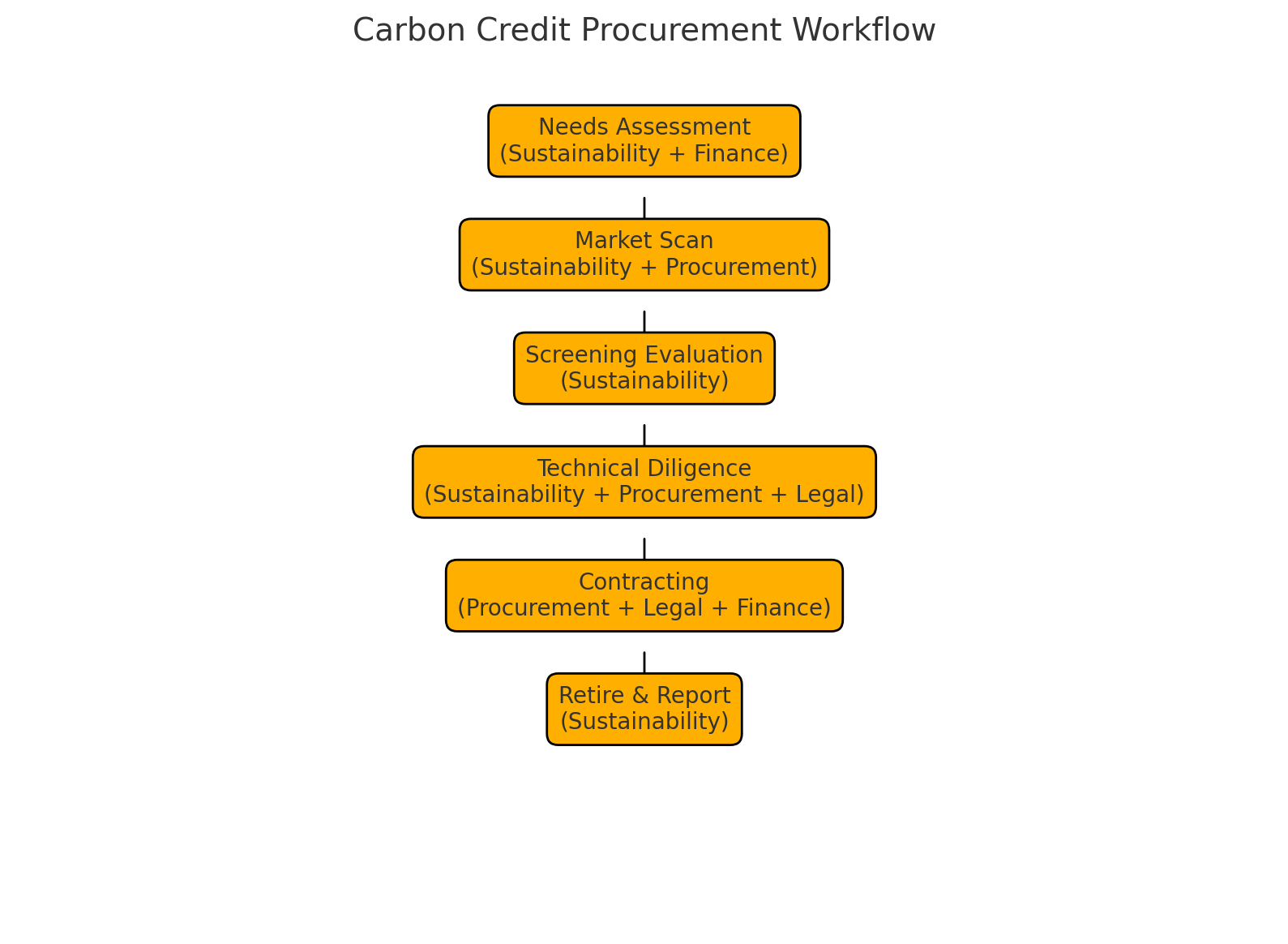

A well-designed carbon procurement workflow ensures organizations purchase high-integrity, auditable credits, and in alignment with the climate strategy.

The first step is Needs Assessment, where Sustainability and Finance have determined the annual credit requirement based on emissions verification data. This calculation should be based on the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard, and only consider residual emissions not capable of abating internally for the near term in line with Science Based Targets initiative recommendations. This process should generally take between two to four weeks, based mostly on the timing to finalize the emissions data.

Once needs are defined, the team now goes to Market Scan to scope a broad pool of potential projects across avoidance, reduction, nature-based removals, and engineered removals. Together, Sustainability and Procurement will review supplier lists and developer pipelines to identify options. The aim is breadth, not selection, and the market scan should be within one to two weeks. This stage must consider both near-term opportunity and long-term supply, and should be informed by pathways reinforced in IPCC mitigation reports.

Shortlisted projects are then subject to Screening Evaluation process where Sustainability applies a standard integrity rubric to each project in evaluating aspects of the project such as: additionality, permanence, MRV rigour, leakage, biodiversity impacts and community consent. This scoring approach should support alignment with the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles to develop a consistent baseline for quality. Screening usually takes between seven and 14 days, resulting in the project being categorised in one of three categories: Eligible, Eligible with Conditions or Not Eligible.

Projects that pass screening move on to Technical Diligence, where the team begins an in-depth review of the project documentation, monitoring reports, baseline assumptions, verification statements and risk exposure. Sustainability leads the analysis; Procurement manages developer engagement; and Legal, evaluates contractual risks and liabilities. Technical Diligence may take between two to six weeks depending on availability of data and efficiently handling complex projects.

Approved projects move into Contracting, which is led by Procurement and in close collaboration with Legal and Finance. Negotiations will centre on terms, pricing, delivery schedules, liability allocation, buffer pool provision and claims language for all environmental claims. Claims language needs to align with the VCMI Claims Code of Practice to prevent any possible exaggeration or misrepresentation in communication.

Finally, credits will be Retired and Reported. Sustainability leads the retirement process through registries (i.e. Verra or Gold Standard) and Reports all credits for alignment with annual sustainability reporting cycle. This is important for transparency, traceability and audit readiness.

6. Common Failure Modes and How to Avoid Them

For instance, many organizations utilize parallel review processes where Sustainability, Procurement, Finance, and Legal evaluate projects in isolation, rather than in a sequenced ownership to model project quality. This regularly creates duplication of diligence work, contradictory decisions, and delays of multiple weeks.

Sometimes companies over rely on third-party rating services to assess project quality without deploying an internal integrity rubric consistent with other potentially guiding principles like the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles, which leads to misalignment when teams discover a project has been externally rated “high quality,” but doesn’t meet internal risk, community, or co-benefit criteria expectations, yet the appearance of the project suggests it should.

Another frequent issue is not linking procurement decisions to public claims which often leads to misrepresentation or exaggeration in sustainability reporting. To avoid this, claims language should align with the VCMI Claims Code of Practice to build credibility while avoiding reputational or regulatory risk.

Likewise, many organizations attempt to maximize their carbon procurement program in year one instead of maturing the ideal procurement steps in a phased approach aligned with Climate Action Plans or net-zero paths as advised by the Science Based Targets initiative. In the early stages, organizations should focus on establishing governance, evaluation criteria, and defensible processes and only then layer in leading or lagging indicators.

Utilizing a playbook does not guarantee perfection it guarantees consistency. Consistency leads to speed, cross-functional alignment, audit ready and trust over time, despite changes in the market norms.

Hestiya embeds these guardrails into a single operating system with the help of iglooai by centralizing data, standardizing evaluation frameworks, and automating governance checkpoints to remove ambiguity and duplication. With structured workflows and audit-ready traceability, teams avoid common pitfalls and accelerate from fragmented decision-making to disciplined, high-integrity carbon procurement.

7. What “Good” Looks Like (Signals of a Mature Carbon Buying Function)

A mature carbon procurement function is characterized not by the size of its portfolio, but by the clarity, repeatability, and defensibility of its processes. Leading organizations tend to maintain an annual portfolio review cycle, aligned to changes in the Science Based Targets initiative guidance, ensuring the purchased credits enable their decarbonization pathway instead of supplanting reductions of internal emissions.

Each project selection is traceable with a clear audit trail outlining the evaluation criteria, stakeholder approval, commercial terms and claims alignment, hitting the governance assumptions defined in the ICVCM Core Carbon Principles.

A mature team can also explain, simply, why every project is selected, not just explain their score, based on internal quality rather than exclusively relying on third-party scoring mechanism. Public claims containing explicit commercial value are structured and reviewed to withstand scrutiny by regulators, investors, and the public, including alignment with guidelines such as the VCMI Claims Code of Practice and evolving regulatory requirements such as the EU Green Claims Directive.

In the end, “good” carbon procurement is not about chasing the perfect credit. It is about building consistency, traceability, and institutional confidence so decisions remain sound as market standards change and new stakeholders, internal and external ask harder questions.

How Hestiya Enables This

While a carbon-buying playbook defines the structure, Hestiya enables organizations to execute it with precision. Hestiya operationalizes carbon procurement end-to-end — standardizing integrity evaluation, consolidating project data, and embedding governance and approval workflows into one platform. Sustainability, procurement, finance, and legal teams gain a shared, evidence-based system for comparing projects, documenting diligence, and making defensible decisions aligned to SBTi, ICVCM, and VCMI frameworks. With expert intelligence, integrated scoring models, and audit-ready traceability, Hestiya converts complex, multi-stakeholder carbon purchasing into a clear, repeatable, and rigorously governed process reducing friction, accelerating cycle times, and strengthening climate integrity across the organization.

8. Conclusion

In a world where climate integrity is scrutinized more than ever, companies can’t rely on ad-hoc or reactive carbon decisions. A structured carbon-buying playbook ensures every investment aligns with science-based pathways, evolving standards, and stakeholder expectations.

The future belongs to organizations that embed climate competence into their operations — not just their commitments.

With Hestiya, organizations build the operational muscle required to turn net-zero ambition into durable, high-integrity outcomes.

References

Net Zero Tracker. Net Zero Tracker Global Corporate Net Zero Database, 2023. https://zerotracker.net

Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit & Oxford Net Zero. Taking Stock: A Global Assessment of Net Zero Targets, 2023.

Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Corporate Net-Zero Standard and Foundations for Net-Zero Target Setting, Science Based Targets initiative, 2021–2023. https://sciencebasedtargets.org

Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM). Core Carbon Principles, Assessment Framework and Assessment Procedure, ICVCM, 2023. https://icvcm.org

Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI). VCMI Claims Code of Practice, VCMI, 2023. https://vcmintegrity.org

McKinsey & Company. A Blueprint for Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, McKinsey Sustainability, 2021.

World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023, World Bank, 2023.

Trove Research. Voluntary Carbon Market Outlook 2023, Trove Research, 2023.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Sixth Assessment Report: Mitigation of Climate Change, IPCC, 2022.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Corporate Standard, World Resources Institute & WBCSD, 2015. https://ghgprotocol.org

European Commission. Proposal for a Directive on Green Claims, European Union, 2023.