The Hidden Cost of Poor Carbon Data: Why Climate Decisions Fail Without Reliable Inputs

Executive summary

Carbon decisions are only as good as the data behind them. When emissions baselines are uncertain, supplier footprints are guessed, or carbon credits lack verifiable impact histories, organizations end up optimizing the wrong levers, sometimes spending millions to “reduce” emissions that were never accurately measured in the first place. Poor carbon data quietly creates three compounding failures:

Strategic failure: targets and pathways are built on shaky baselines, leading to under- or over-investment.

Financial failure: capital is misallocated; procurement pays premiums for low-integrity claims; compliance and audit costs rise.

Credibility failure: disclosures, marketing claims, and offset strategies are challenged by stakeholders, regulators, and markets.

The evidence is already visible in the real world: only a small fraction of companies score as “high quality” environmental disclosers, and many commonly used carbon credits have been found to deliver far less real-world impact than claimed.1

This report explains how poor carbon data breaks decision-making, quantifies the business impact using credible statistics, and proposes a practical framework for building data that can withstand financial-grade scrutiny.

1) What “carbon data” actually includes

Most teams think carbon data means “Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.” In practice, decision-grade carbon data is a system, a chain of inputs, assumptions, controls, and audit trails that connects operational reality to reported numbers. It includes:

Activity data: fuel used, electricity consumed, distance traveled, materials purchased, production volumes.

Emission factors: grid intensities, material factors, logistics factors (and their versioning over time).

Organizational boundaries: what’s included/excluded (subsidiaries, joint ventures, franchise models).

Methodologies & calculation logic: consistent application of protocols, treatment of uncertainty.

Verification evidence: source documents, controls, change logs, approvals.

Market instruments data: I-RECs, carbon credits, issuance, ownership, retirement, and claims alignment.

Disclosure outputs: filings and reports expected to be consistent, comparable, and decision-useful.

Standards like the GHG Protocol explicitly emphasize inventory quality management, uncertainty, and systems to reduce bias, because without those controls, emissions numbers become “spreadsheet opinions.”2

Meanwhile, sustainability disclosure is moving closer to financial reporting. IFRS/ISSB standards (IFRS S1 and S2) formalize structured requirements across governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics/targets, increasing pressure for traceable inputs and consistent methodologies.3,4

2) The hidden costs: where poor carbon data hurts most

A) Misallocated capital and “false optimization”

When emissions hotspots are misidentified, teams invest in projects that look good on paper but don’t move real-world outcomes.

Common examples:

Switching suppliers based on modeled footprints that rely on generic emission factors rather than primary supplier data.

Funding efficiency projects that reduce measured emissions but not actual emissions because baseline energy data was incomplete.

Setting internal carbon prices or marginal abatement curves that prioritize the wrong abatement options.

Hidden cost: wasted spend + missed reduction opportunities + delayed progress.

B) Higher cost of capital and risk premiums

Poor data increases perceived risk. Investors and lenders care about:

consistency over time,

comparability across peers,

and whether numbers can be audited.

If disclosures are weak, companies may face:

tougher diligence,

higher cost of capital,

and reduced investor confidence.

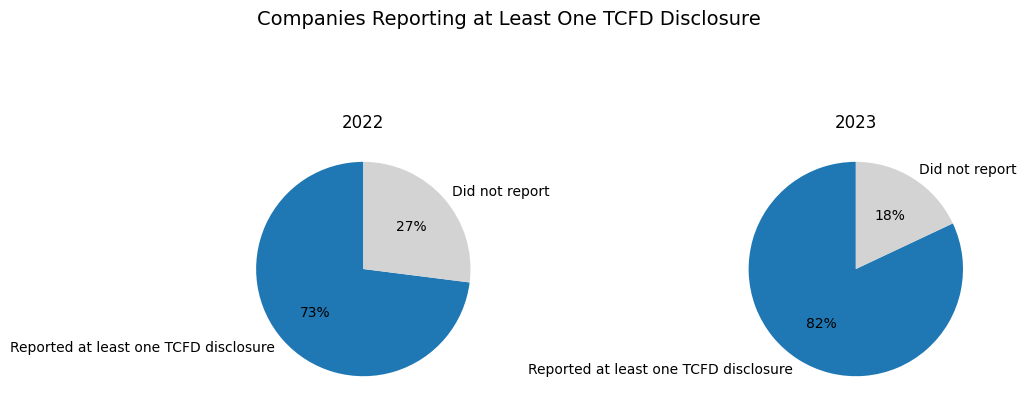

The trend toward structured climate disclosure reinforces this: more companies are disclosing climate information, but comprehensive disclosure remains uneven. In a large sample, the share of firms reporting at least one TCFD-aligned disclosure increased year-over-year, showing momentum, but also signaling that markets will expect more completeness over time.5,6

C) Compliance and reporting churn

As regulators and frameworks mature, poor inputs lead to expensive reporting cycles:

repeated restatements,

inconsistent year-to-year numbers,

and “audit scramble” to find evidence.

Hidden cost: time, external assurance fees, internal burnout, and slower decision cycles.

D) Integrity failures in offsets and carbon credits

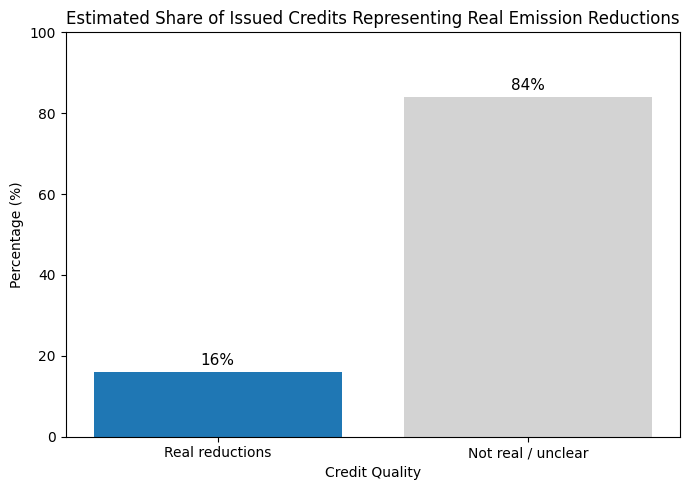

Offset quality is a carbon data problem as much as a climate policy problem: credit buyers need reliable project baselines, monitoring data, additionality tests, and safeguards against double counting.

Recent research highlights systemic issues in credited reductions. A Nature Communications assessment estimated that less than 16% of issued credits across the investigated projects represented real emission reductions.

Separately, integrity bodies have raised the bar: the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) determined that credits from current renewable energy methodologies would not receive its high-integrity label, citing insufficient rigor around additionality.7,8

Hidden cost: you can spend money and still fail to create credible climate impact, while taking on reputational and even legal risk.

3) The current landscape in numbers

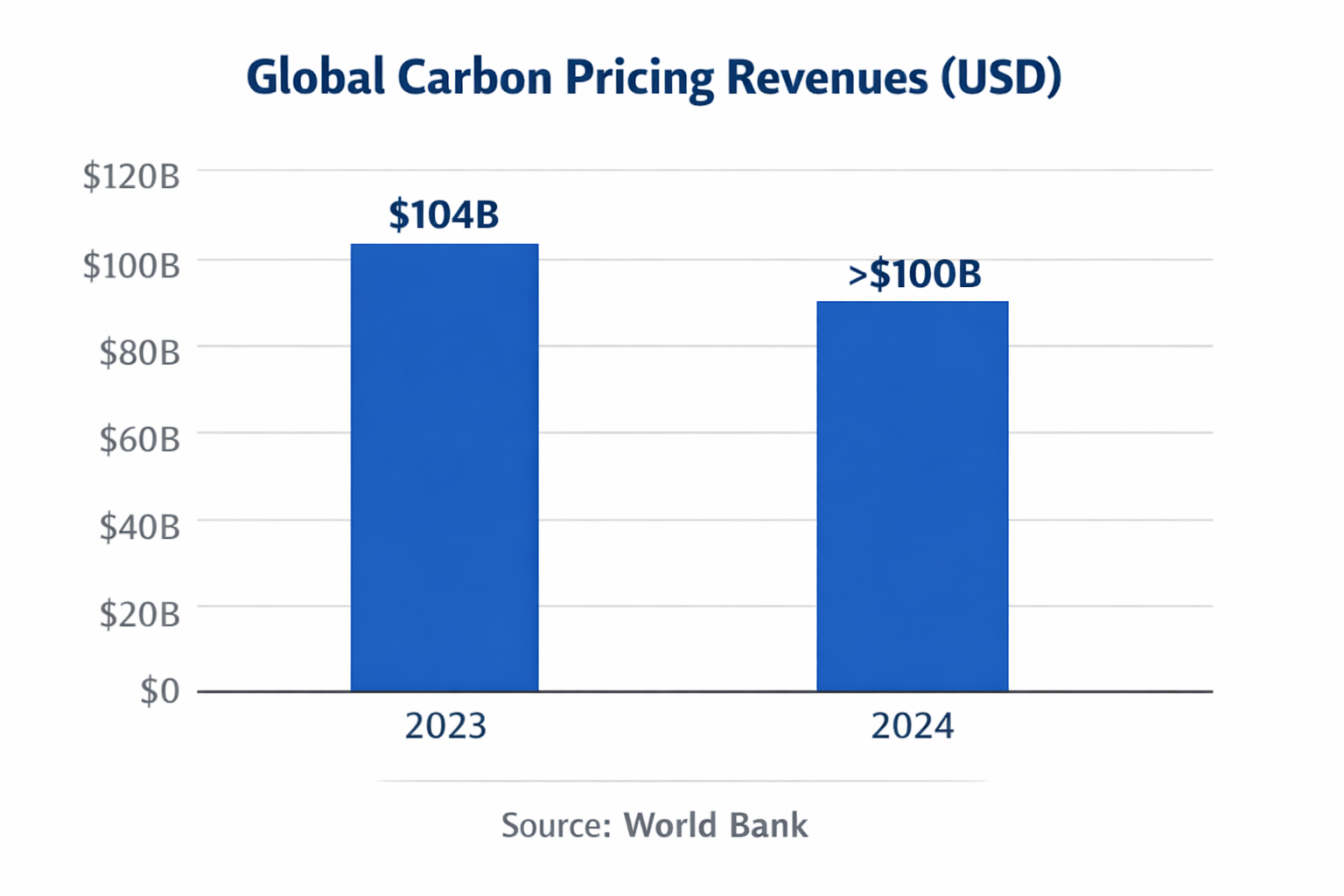

Chart 1: Carbon pricing revenues show the financial stakes

World Bank reporting shows carbon pricing is now a $100B+ per year reality, meaning measurement, verification, and accounting infrastructure increasingly matters.

Chart 2 , Climate disclosure is rising, but completeness is still limited

In an IFRS report (tracking TCFD-aligned disclosure patterns), the percentage of companies disclosing at least one recommended disclosure rose from 73% (2022) to 82% (2023), but “all disclosures” remained rare.6,7

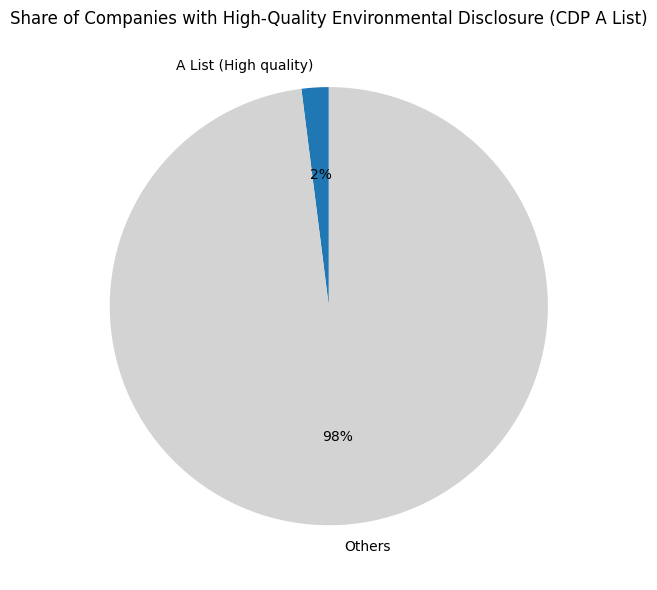

Chart 3 , “High-quality disclosure” is still the exception

CDP scored 21,000+ companies and reported that ~2% achieved its 2023 “A List” status for actionable, high-quality environmental disclosure.8

Chart 4: Offset integrity: measured impact vs. credited impact

A systematic assessment estimated <16% of credits issued to investigated projects constituted real emission reductions, suggesting how badly decisions can fail when underlying data and assumptions are weak.9,10

4) Why climate decisions fail: the five data failure modes

Failure mode : “Garbage-in baselines”

If the base year inventory is incomplete or inconsistent, every target and roadmap built on it becomes unstable.

Typical causes:

missing sites, missing SKUs, missing suppliers,

inconsistent organizational boundaries,

activity data gaps filled with rough estimates.

Result: the business believes it is reducing emissions when it may only be improving measurement, or vice versa.

Failure mode 2: Overreliance on generic emission factors

Emission factors are necessary, but overusing secondary databases where primary data is available produces false precision.

Examples:

average grid factors applied to contracted renewable electricity without accurate market-based accounting evidence,

average material factors used for specialty inputs with unique production routes.

Result: wrong hotspot ranking → wrong abatement priorities.

Failure mode 3: Broken traceability and weak audit trails

Without a documented trail, teams cannot prove:

where numbers came from,

who approved changes,

and which methodology version was used.

GHG Protocol guidance emphasizes managing inventory quality and uncertainty because systematic uncertainty and bias can be reduced with robust quality management systems.

Result: assurance costs spike, disclosures get challenged, and internal trust declines.

Failure mode 4: Double counting and claim confusion

Double counting isn’t just a market design problem; it’s a data architecture problem.

Examples:

two entities claiming the same reduction (buyer and host country; or within supply chains),

unclear retirement status,

inconsistent registries or identifiers.

Market observers and policy papers continue to highlight double counting and fragmentation risks, especially in voluntary markets.

Result: the organization overstates progress and risks reputational damage.

Failure mode 5: Misaligned incentives and “checkbox reporting”

When the goal becomes “publish a number” rather than “manage emissions,” teams optimize for passing disclosure instead of improving data integrity.

CDP’s A List statistic (only ~2%) is an indicator that achieving actionable, high-quality disclosure remains difficult and uncommon at scale.

Result: climate becomes a communications exercise rather than an operating system.

5) Poor data doesn’t just create errors: it changes behavior

A subtle but damaging effect of low-quality data is decision avoidance:

Procurement teams hesitate to change suppliers if footprint comparisons feel unreliable.

Finance teams won’t embed carbon into investment decisions if they don’t trust the numbers.

Executives delay action, waiting for “better data,” while emissions and regulatory pressure continue to rise.

In other words: poor carbon data creates a confidence gap, and the confidence gap becomes a progress gap.

6) What “reliable inputs” look like: a decision-grade carbon data framework

Here’s a pragmatic model many organizations are moving toward, think of it like upgrading from “spreadsheet reporting” to “financial-grade data.”

Layer : Governance (who owns what)

Named owners for Scope 1, Scope 2, Scope 3 categories.

Data stewards for emission factors and methodology updates.

A clear approval workflow for inventory changes.

This aligns with the structure expected in modern disclosure regimes that emphasize governance and risk management integration.

Layer 2: Controls and documentation (how you prove it)

Evidence library: invoices, meter data, fuel receipts, supplier declarations.

Versioned calculation logic and emission factors (with timestamps).

Change logs: what changed, why, who approved.

Layer 3: Data quality scoring (how you manage uncertainty)

Score each data stream (primary vs secondary, completeness, timeliness).

Quantify uncertainty where feasible using accepted guidance.

Prioritize upgrades where decisions are most sensitive.

GHG Protocol uncertainty guidance exists specifically to make this systematic rather than ad hoc.

Layer 4: Traceability across market instruments (credits, I-RECs)

For carbon credits especially:

require registry IDs, issuance dates, retirement proof,

map claims to purpose (residual emissions vs beyond value chain),

document quality screens and methodology decisions.

ICVCM’s actions around methodology quality illustrate why buyers can’t treat credits as interchangeable commodities.

7) Recommendations: How to fix carbon data without boiling the ocean

1) Start with decision-critical use cases

Pick 2–3 decisions where carbon data materially changes outcomes:

supplier selection for top categories,

capex prioritization,

product footprint claims,

credit procurement strategy.

2) Build a “minimum viable audit trail”

Before perfect accuracy, ensure you can answer:

Where did this number come from?

What evidence supports it?

What assumptions were used?

Who approved changes?

3) Treat Scope 3 like a data product

Segment suppliers by spend and emissions relevance.

Require primary data from top tiers; use modeled data only for the long tail.

Create supplier data templates and validation checks.

4) Don’t buy credits you can’t explain

Given the evidence of quality variability, implement a procurement rulebook that requires:

additionality rationale,

monitoring and verification transparency,

leakage and permanence safeguards,

and clear retirement documentation.

Research showing low realized reductions in many investigated credits is exactly why this rigor matters.

5) Align finance, sustainability, procurement, and legal

Carbon decisions fail when teams operate in silos. Create one integrated workflow:

sustainability defines requirements,

procurement embeds them in contracting,

finance links to investment cases,

legal/comms governs claims.

The Role of Hestiya in Enabling Decision-Grade Carbon Data

In this evolving landscape, platforms like Hestiya play a critical role in closing the gap between carbon reporting and decision-ready intelligence. Hestiya is built to help organizations move beyond fragmented spreadsheets and compliance-driven disclosures toward structured, auditable, and decision-grade carbon data systems. By integrating emissions data, carbon credit information, and governance workflows into a single, transparent framework, Hestiya enables companies to trace data back to its source, validate assumptions, and maintain consistent audit trails. Its focus on data integrity, traceability, and lifecycle transparency supports better procurement decisions, more credible climate claims, and stronger alignment with emerging regulatory and investor expectations. In doing so, Hestiya helps organizations shift from reactive reporting to proactive climate governance.

Conclusion: Carbon data is climate infrastructure

The “hidden cost” of poor carbon data is not just bad reporting, it’s failed strategy, wasted capital, slower execution, and damaged trust. The market signals are clear: carbon is now financial (e.g., $100B+ in annual carbon pricing revenues) and disclosures are becoming more standardized and decision-oriented 12,13

Organizations that treat carbon data as a governed, traceable, quality-managed system will make faster and more credible decisions, while those that treat it as an annual reporting exercise will keep paying the penalty in money, time, and credibility.

References

Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). CDP Scores and A Lists 2023. CDP Worldwide, 2023, https://www.cdp.net/en/companies/companies-scores.

Financial Stability Board. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). 2017, https://www.fsb-tcfd.org.

GHG Protocol. Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard. World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2004, updated editions, https://ghgprotocol.org/corporate-standard.

GHG Protocol. Guidance on Uncertainty Assessment in GHG Inventories and Calculating Statistical Parameter Uncertainty. World Resources Institute, https://ghgprotocol.org.

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation. IFRS S1: General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information. 2023, https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/ifrs-sustainability-standards-navigator/ifrs-s1-general-requirements-for-disclosure-of-sustainability-related-financial-information/.

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation. IFRS S2: Climate-related Disclosures. 2023, https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/ifrs-sustainability-standards-navigator/ifrs-s2-climate-related-disclosures/.

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation. Progress on Climate-related Disclosures. IFRS Foundation, 2024, https://www.ifrs.org.

Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM). Core Carbon Principles and Assessment Framework. 2023, https://icvcm.org.

Nature Communications. Calel, Raphael, et al. “Systemic Over-crediting in Carbon Markets.” Nature Communications, vol. 15, 2024, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-XXXX-X.

World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2024. World Bank Group, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon.

World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023. World Bank Group, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon.

World Economic Forum. Net-Zero Challenge: The Supply Chain Opportunity. World Economic Forum, 2023, https://www.weforum.org.

Financial Markets Standards Board (FMSB).Statement on Voluntary Carbon Markets and Market Integrity. 2023, https://fmsb.org.uk.